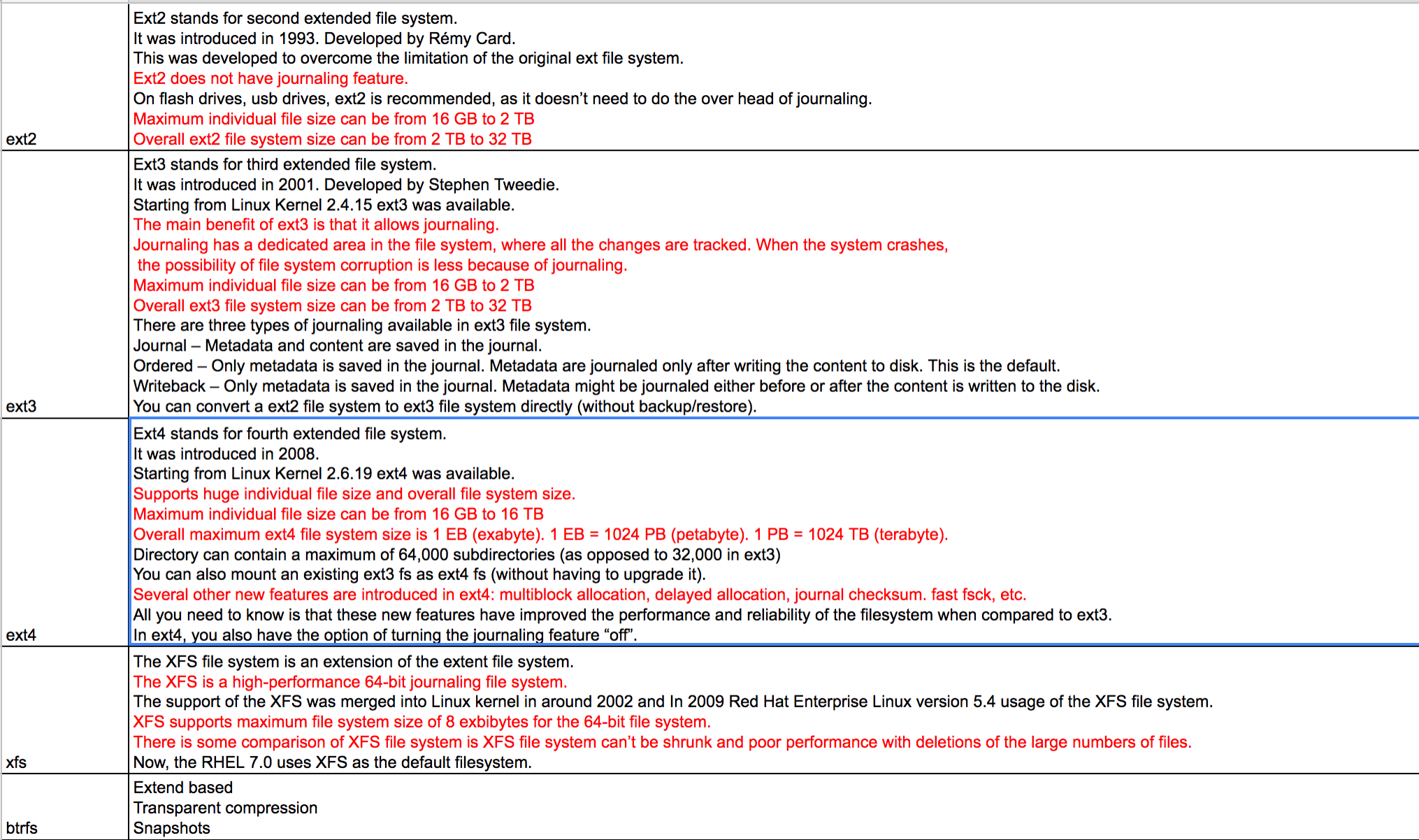

File System

(°0°)

(°0°)

ext4 tuning:

noatime(no access timestamp),noatime > relatime > atime

nobarrier(Write barriers enforce proper on-disk ordering of journal commits, making volatile disk write caches safe to use, at some performance penalty)

writeback(only metadata being journaled, but not actual file data)

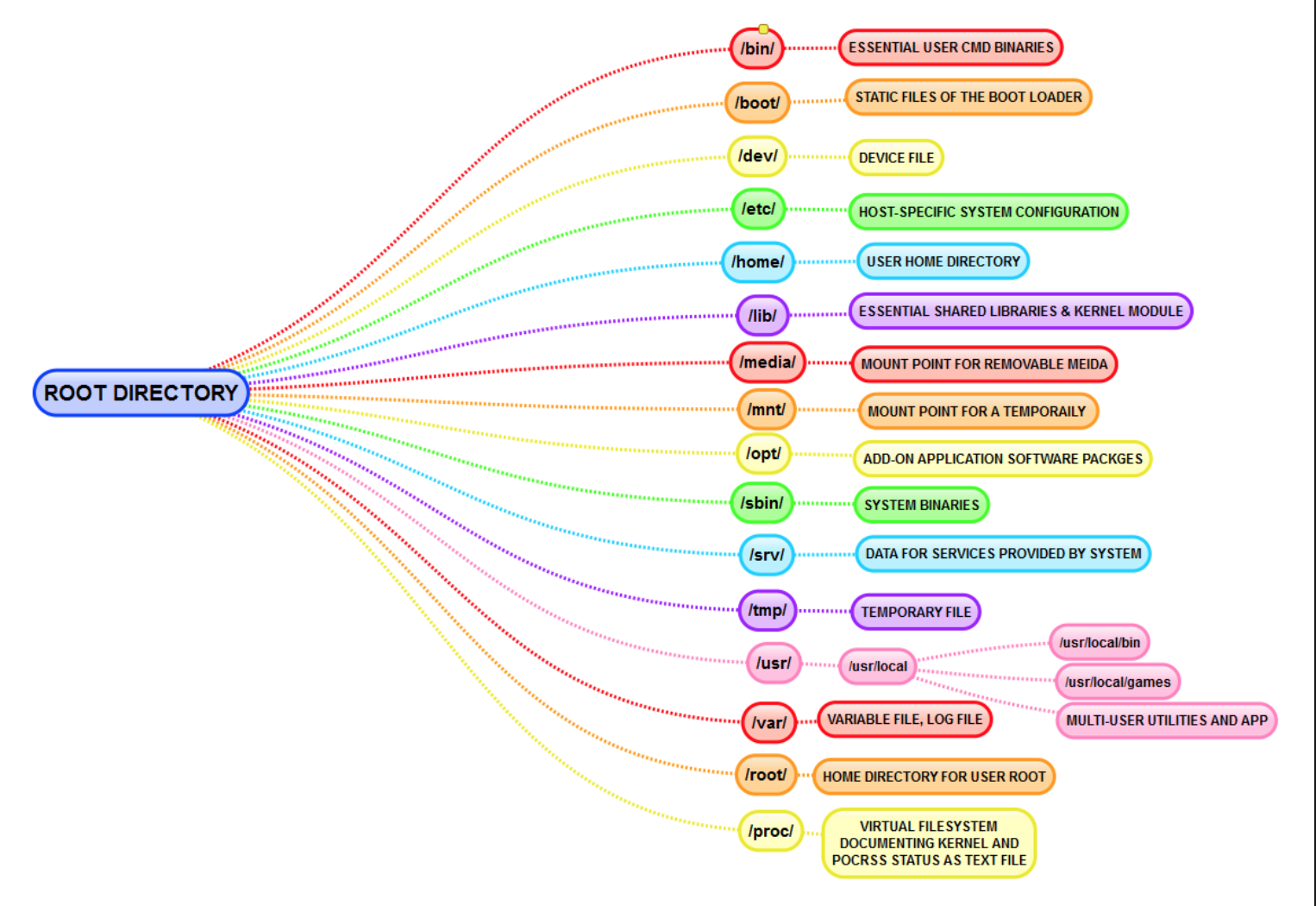

File Directory

(°0°)

(°0°)

Inode

For each file (and directory) in Linux there is an inode, a data structure which stores meta data related to the file like its size, owner, permissions,

etc.

df -i

ls -li

Hardlink and Softlink

- Hard link is the same file, using the same inode. Soft link is a shortcut to another file, using a different inode.

- Directories always have mini 2 links

- soft link

can cross the file system, allows you to link between directories, has different inode number and file permissions than original file, permissions will not be updated, has only the path of the original file, not the contents. - hard link

can't cross the file system boundaries (i.e. A hardlink can only work on the same filesystem), can't link directories, has the same inode number and permissions of original file, permissions will be updated if we change the permissions of source file, has the actual contents of original file, so that you still can view the contents, even if the original file moved or removed.

mount

- command

mount cat /proc/mounts df -T - lazy mount

Lazy unmount detaches the filesystem from system hierarchy and clean up all references to our filesystem as soon as it is not busy

```

Force umountumount -f

Lazy Umount

umount -l

**swap space**

The primary function of swap space is to substitute disk space for RAM memory when real RAM fills up and more space is needed.

2 times of RAM

Linux has two forms of swap space: the swap partition and the swap file. The swap partition is an independent section of the hard disk used solely for swapping; no other files can reside there. The swap file is a special file in the filesystem that resides amongst your system and data files

mkswap

swapon -s

**tmpfs**

Tmpfs is a file system which keeps all of its files in virtual memory, mounted as shared memory /run, The /run directory and its sub-directories store run time data of Linux processes and any running applications that may want to store their data. /dev/shm, It normally is used to transfer data between programs.

**tmp**

/tmp is cleared upon system boot while /var/tmp is cleared every a couple of days or not cleared at all (depends on distro).

**File**

1. create a file with given size

dd if=/dev/zero of=upload_test bs=1M count=size_in_megabytes

truncate -s 5M ostechnix.txt

head -c 5MB /dev/zero > ostechnix.txt

**resizing**

fdisk /dev/sdb

fsck /dev/sdb

resize2fs /dev/sdb3

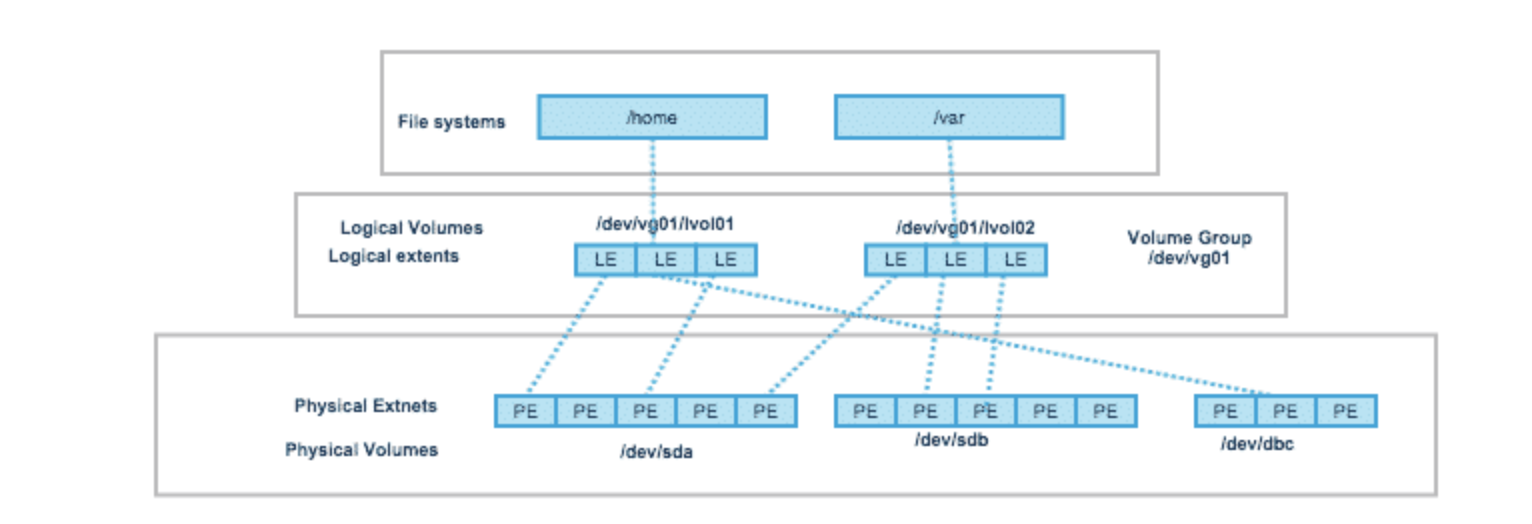

**LVM**

{: .center-image }*(°0°)*

1. Logical volume manager (LVM) introduces an extra layer between the physical disks and the file system allowing file systems to be :

– resized and moved easily and online without requiring a system-wide outage.

– Using discontinuous space on disk

– meaningful names to volumes, rather than the usual cryptic device names.

– span multiple physical disks

2. PV, VG, LV

- PV, Each Physical Volume can be a disk partition, whole disk, meta-device, or a loopback file.

- VG, A Volume Group gathers together a collection of Logical Volumes and Physical Volumes into one administrative unit. Volume group is divided into fixed size physical extents(PE).– The default size of PE is 4MB, but you can change it to the value you want at the time of VG creation. Generally, larger the PE size, better the performance (though less granular control of LV).

- LV, A Logical Volume is the conceptual equivalent of a disk partition in a non-LVM system. Logical volumes are block devices which are created from the physical extents present in the same volume group.

3. Filesystem, File systems are built on top of logical volumes.

4. steps to create

- Create 3 Physical volumes from 3 physical disks (/dev/sdb, /dev/sdc, /dev/sdd).

- Create Volume group from these 3 PVs (/dev/vg01).

- Create a Lgical Volume in this VG (/dev/vg01/lvol01).

- Create a File system on this LV and mount it (/data01).

```

refer

NFS

An NFS is a protocol that lets users on client computers access files on a network, making it a distributed file system.

HDFS

refer

fuse_dfs_wrapper.sh

hadoop-fuse-dfs#dfs://hdp-dfs:8020 /hdfs/data fuse _netdev,nodev,noexec,nosuid,ro,allow_other,modules=subdir,subdir=/data

RAID

RAID is a technique of combining multiple partitions in separate disks into a single large device or virtual storage unit. These units are called RAID arrays. disk mirroring (RAID Level 1), disk striping (RAID Level 0, one data on two separate disks), and parity are some examples of RAID techniques.

Redundancy: If one disk crashes, the data is duplicated on other disks, preventing data loss.

Performance: By writing data to several disks, the overall data transfer rate can be increased.

Convenience: Setting up RAID is simpler, and storage from several physical disks can be handled even though they are in different systems.

- Hardware Raid

Hardware RAID is implemented independently on the host. This means that you’ll have to spend extra cost on hardware to get it up and running.They are, of course, fast and they have their dedicated RAID controller, which is supplied by the PCI express card. - Software Raid

In the case of software RAIDs, the operating system is responsible for everything.

log/var/log/syslog or /var/log/messages: general messages, as well as system-related information. Essentially, this log stores all activity data across the global system. Note that activity for Redhat-based systems, such as CentOS or Rhel, are stored in messages, while Ubuntu and other Debian-based systems are stored in Syslog. /var/log/auth.log or /var/log/secure: store authentication logs, including both successful and failed logins and authentication methods. Again, the system type dictates where authentication logs are stored; Debian/Ubuntu information is stored in /var/log/auth.log, while Redhat/CentrOS is stored in /var/log/secure. /var/log/boot.log: a repository of all information related to booting and any messages logged during startup. /var/log/maillog or var/log/mail.log: stores all logs related to mail servers, useful when you need information about postfix, smtpd, or any email-related services running on your server. /var/log/kern: stores Kernel logs and warning data. This log is valuable for troubleshooting custom kernels as well. /var/log/dmesg: messages relating to device drivers. The command dmesg can be used to view messages in this file. /var/log/faillog: contains information all failed login attempts, which is useful for gaining insights on attempted security breaches, such as those attempting to hack login credentials as well as brute-force attacks. /var/log/cron: stores all Crond-related messages (cron jobs), such as when the cron daemon initiated a job, related failure messages, etc. /var/log/yum.log: if you install packages using the yum command, this log stores all related information, which can be useful in determining whether a package and all components were correctly installed. /var/log/httpd/: a directory containing error_log and access_log files of the Apache httpd daemon. The error_log contains all errors encountered by httpd. These errors include memory issues and other system-related errors. access_log contains a record of all requests received over HTTP. /var/log/mysqld.log or /var/log/mysql.log : MySQL log file that logs all debug, failure and success messages. Contains information about the starting, stopping and restarting of MySQL daemon mysqld. This is another instance where the system dictates the directory; RedHat, CentOS, Fedora, and other RedHat-based systems use /var/log/mysqld.log, while Debian/Ubuntu use the /var/log/mysql.log directory.Permission

- permission groups: owner,group,all users

- permission types: read,write,execute

- ls -l

_rwxrwxrwx 1 owner:groups # the first character is a special permission flag # others are for owner,group and users # <1> number of hardlinks to the file # owner:group - chmod , chmod a-rw file1

```

u – Owner

g – Group

o – Others

a – All users

- plus

- minus

r – Read

w – Write

x – Execute

r = 4

w = 2

x = 15. advanced permissions_ – no special permissions

d – directory

l– The file or directory is a symbolic link

s – This indicated the setuid/setgid permissions. This is not set displayed in the special permission part of the permissions display, but is represented as a s in the read portion of the owner or group permissions.

t – This indicates the sticky bit permissions. This is not set displayed in the special permission part of the permissions display, but is represented as a t in the executable portion of the all users permissions

```

The setuid/setguid permissions are used to tell the system to run an executable as the owner with the owner’s permissions.

The sticky bit can be very useful in shared environment because when it has been assigned to the permissions on a directory it sets it so only file owner can rename or delete the said file.- important files

home directory 700

bootloader configuration files 700

system and daemon config files 644

firewall scripts 700

- important files